The Art of Fire

- by Davood Arsouni

- Member of the Editorial Board

- Contact Email: arsooni@gmail.com

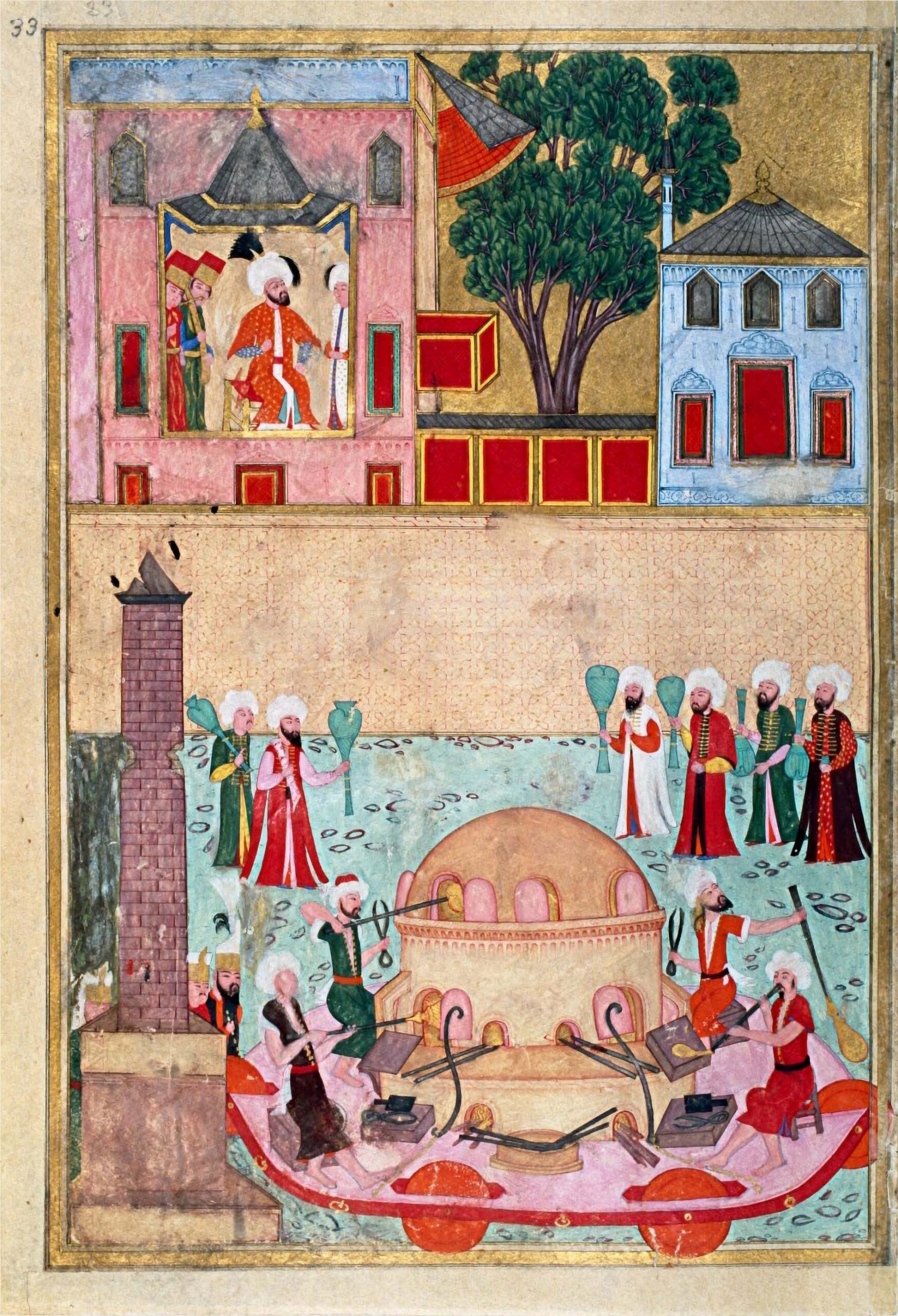

In the painting The Glassblower’s Show at the Constantinople Racecourse from the book Surname-i Hümayun[1], a magnificent moment of the ancient art of glassblowing is depicted. This painting not only narrates the process of creating glass goblets but also represents the combination of the four elements—earth, water, wind, and fire—in a harmonious dance. These elements have been symbols of creativity and vitality in both ancient Eastern mythology and literature.

Earth, which provides the raw material for glass production in the form of siliceous sands, plays the initial role in this cycle. Water, the element that brings coolness to the heat of fire, harmonizes each stage of the process and bestows the final coolness to the structure of the goblets. Wind, the life-giving and creative force present in every breath of the artist, transforms the form from chaos to order. And fire, the force that melts all these materials and enables their formation, symbolizes change and transformation.

The Ottoman painting, with its delicate attention to detail, captures the moment when the glassblower, by blowing through a metal pipe, transforms lifeless sand particles into a shining and transparent object. This scene does not only depict a craft; it illustrates a profound connection with nature, wherein the artist engages in an inspiring dialogue with the four elements.

The artist glassblowers in the painting have mounted their furnace on a massive carriage so that the sultan, away from the heat of the fire, can watch their artistry from the pavilion and see how his crystal goblets filled with wine are created. How art rises from the heart of the fire, cools, and travels lightly to different parts of the world in the hands of the sultan.

The Art of Glassblowing and Ancient myth

In Eastern cultures, the four elements are at the core of philosophical and mythological beliefs. In ancient Iran, these elements were not just parts of nature but were also considered divine forces that created and preserved the world. Glassblowing, by combining these elements, is reminiscent of ancient lore in which mythical creators brought the world into existence by breathing life into form.

When we look at glass goblets, we are not facing a lifeless object. These works are the manifestation of the connection between nature and humans. The elements of earth, water, wind, and fire, present in every stage of glass production, remind us of nature’s creative power. In Persian literature, wind and fire are symbols of divergence and evolvement. In mystical poetry, the wind symbolizes movement and change, while fire represents purity and transmutation. The combination of these two elements transforms glassblowing into art; an art that not only changes the form but also transforms the viewer’s soul.

Then, water comes along to cleanse and complete the process. The moment the glassblower, immerses the goblet in water, is a reminder of the act of rebirth in Eastern myths.

This action signifies a return to the primal essence and inherent purity of materials.

Every breath of the glassblower embodies a spirit reminiscent of the breaths of the world’s mythical creators. These goblets, once mere lifeless particles of earth, have now taken their clearest and most brilliant form. They narrate a story of rebirth; a story that begins amid the flames and a breath of wind. In the end, the spirit of nature is reflected in its transparency.

This poetic perspective on glassblowing art is not only rooted in the history of an ancient craft but also opens a window to contemplation about the relationship between humans and nature and the fundamental elements of life. Glass serves as a mirror that reminds us of the eternal and timeless powers of nature; the same powers that have been the cause and sustainers of life since the beginning of the world.

The Passage of Glass from East to West: An Eternal Link Between Cultures

Glassblowing was more than just a local art form; it became a bridge connecting cultures and civilizations. Techniques such as colorless glass cutting, first executed in the Eastern Mediterranean, made its way to the West in the ninth century. Syrian cities like Raqqa and Damascus were centers for producing glassware with enamel decorations, which later influenced Venice, the hub of Western glassblowing art. The blowing wind of Eastern glassblowers did more than shaping goblets. It played a role in transferring glassblowing techniques to the West. Inspired by these methods, the Venetians revived their glassblowing art. This transfer of techniques is a story of cooperation between civilizations and the sharing of knowledge hidden behind the transparent layers of glass.

In the valuable book Bazaar to Piazza[2] by Rosamond Mack, a story of extensive exchange between the Islamic world and Europe during the Renaissance is narrated. It recounts how art and craft turned into a bridge for communication between two different spheres. These exchanges began in the twelfth century, during the Crusades, and continued until the sixteenth century and beyond. Glass, like other arts such as weaving, ceramics, and metalworking, was one of the main axes of this exchange.

In this context, the Mediterranean played a key role; a natural bridge through which raw materials, techniques, and ideas were transferred from East to West. For instance, in 1277, documents show that even the amount of broken glass sent from Tripoli to Venice for use in glass-making workshops was recorded. This close cooperation shows how Western artisans relied on Eastern materials and methods to revive their art. However, by the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Venetian glassblowers had succeeded in learning advanced Syrian glass-making techniques and producing in such a way that they no longer needed to compete with Islamic glassblowers.

Eastern Techniques: Inspirations for the West

Eastern glassblowing techniques, including colorless crystal cutting and enamel methods developed in cities like Damascus and Raqqa, transformed not only glassblowing art in Venice but throughout Europe. These methods, which first blossomed in the ninth century in the Eastern Mediterranean, were transferred to Venice and other parts of Europe through the migration of Eastern artisans, revitalizing Western glass industries. Glassblowing, which had peaked during Roman times, was preserved in the Eastern Mediterranean after the fall of Rome and reintroduced to medieval Europe by Eastern workers.

Similarly, exchanges of the sort can be observed in ceramics. Cobalt blue pigment, known for centuries in the East, found its way to Italy in the early fifteenth century. This material, known as Colore damaschino or Damascus pigment, was smuggled from the East to Venice. Another technique, involving the use of tin oxide to create opaque glazes, was initially developed by Iraqi potters in the ninth century and revitalized European ceramics such as majolica and delftware. These techniques were transferred from Iran and the Middle East to the West, inspiring European artists from the fourteenth century onwards.

The Mutual Impact of Cultures on Daily Life

Between the tenth to the sixteenth centuries, the daily lives of Europeans were profoundly influenced by Islamic technologies and arts. They constantly looked to the East for inspiration in art and prosperity. This was in spite of the often hostile political relationships between the two realms, especially during the Ottoman Empire, when Turkish armies besieged major European cities. Despite these tensions, artistic and cultural connections between East and West not only ensured the survival of the arts but also led to progress and innovation in both sides. The story of glassblowing, with its deep Eastern roots and transformation in the West, reminds us that art is a universal language; one that transcends geographical and political limitations and creates an eternal bond between cultures.

This art emerges from fire, cools, and becomes a vessel for drinking the essence of life, or to warm the body again with the wine it delivers. Only this time it is not in the hands of the sultan alone but for all people to enjoy. This is the same cycle of water, fire, wind, and earth that continues to flow.