From Bonsai to the Socotra Dragon Tree

- by Guest Contributor: Dr. Amir Beshkani, National Museum of Natural History, Paris.

There seems to be something poetic in bonsai[1], something akin to the rows of verses in its branches that turn it into a Haiku-like poem. The intricately arranged lines of this orderly form appear to seduce the viewer’s gaze toward the upper three-quarters of the frame, leaving the lower quarter, or the roots, intentionally overlooked in a relatively small container. I believe that in this minimalist manifestation, the act of bonsai sharply contrasts with the concept of “return”[2]— the return of roots, the all-encompassing return of buds. It’s as if the act of bonsai restricts and predefines the new state (synthesis).

While Heidegger does not explicitly explore “exteriorization” in Being and Time (Sein und Zeit)[3] , this concept can be inferred from his broader philosophical ideas. Dasein, or “being-there,” represents human existence as fundamentally intertwined with the world, always engaged with its surroundings and inseparable from the “Other.” Through this ongoing interaction, Dasein continuously exteriorizes itself—manifesting its being through actions, choices, and relationships. In this light, bonsai transcends its botanical form, symbolizing this process of exteriorization, where Dasein’s essence is expressed in the deliberate shaping of nature. Gestaltung, meaning the act of shaping or forming, perfectly captures the essence of bonsai as an external expression of Dasein’s inner world. In the careful crafting of a bonsai tree, we see Dasein’s engagement with its being-in-the-world, an embodiment of how it shapes and forms both itself and its environment. The bonsai thus becomes more than just a tree; it is a living metaphor for Dasein’s ongoing project of self-formation and world-formation, reflecting the intricate dance between being and becoming.

- Bonsai and Care

Bonsai serves as a profound symbol of Dasein’s interaction with the world into which it is thrown. The art of bonsai mirrors the being-in-the-world of the people of the Far East, as they actively shape and organize something external to themselves. This minimalist recreation can be seen as the exteriorization of Dasein within a specific cultural and temporal context. In this act of creation, Heidegger’s concept of “care” (Sorge) is vividly expressed in Dasein’s relationship with the world. “Care” involves imbuing the external world with meaning, but in the context of bonsai, this care takes on a peculiar form. In bonsai, care paradoxically includes cutting young roots, pruning newly sprouted stems that deviate from the intended design, and wiring older branches to achieve a desired form. This process forces a tree to become something it is not[4] . One might argue that the relationship between Dasein and the tree in the practice of bonsai does not evolve into a dialectical, reciprocal interaction where Dasein (thesis) and being-in-the-world (antithesis) engage in dynamic tension, leading to the formation of a new state (synthesis)[5]. Instead, the art of bonsai can be seen as a one-sided imposition of form, where Dasein’s care constrains the natural growth of the tree, preventing the emergence of a truly dialectical synthesis.

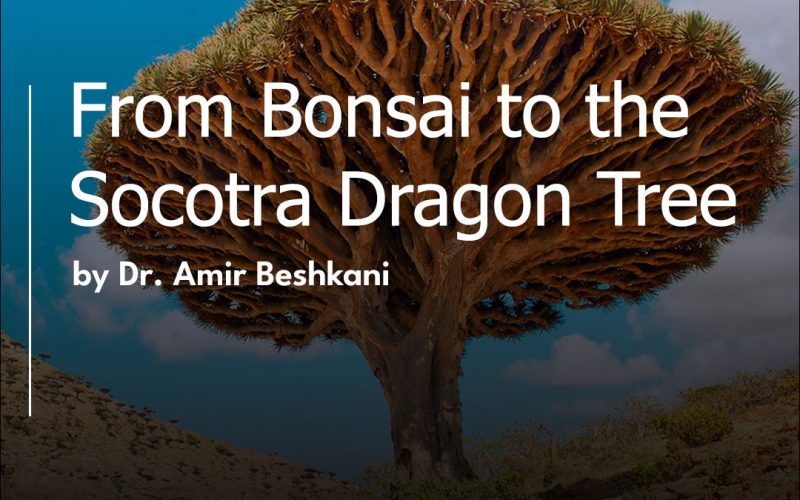

In bonsai, the annual pruning of roots and newly sprouted branches prevents the formation of a new state (synthesis), and the process continues only within the confines of metal wires, leaving the synthesis severely restricted to the lower quarter of the frame. It’s as if these pots, which sometimes forcibly bind the tree and its roots with wires, conceal something repressed within them something that cannot tolerate young roots and misplaced buds, treating their return as a nightmare that must be severed[6]. Therefore, while a bonsai shrub may represent the pinnacle of beauty and be seen as a coexistence of opposites or a pursuit of perfection, I still have my doubts about the practice of bonsai. I find the Socotra Dragon Tree, with its neutral and natural expression, far more appealing. While a bonsai shrub may be celebrated as the pinnacle of beauty, embodying a delicate coexistence of opposites or the pursuit of perfection, this practice raises doubts. The forced restraint and manipulation inherent in bonsai suggest a deeper tension, one that challenges the harmonious integration of opposites. In contrast, the Socotra Dragon Tree, with its neutral and natural expression, offers an unrestrained beauty that feels more authentic and appealing. The Dragon Tree stands as a symbol of nature’s true form, untouched by the constraints of human intervention, representing a more organic and perhaps more genuine synthesis of growth and form.

- The Socotra Dragon Tree and the Zero Degree of Writing

In his book The Zero Degree of Writing (Le Degré zéro de l’écriture, 1972), Roland Barthes describes a type of writing that distances itself from all stylistic and linguistic features, striving to achieve a neutral and impartial state.

Barthes examines naturalism as a writing style that aims to represent reality objectively, stripping away literary embellishments to portray life directly. This form of writing, according to Barthes, employs precise descriptions and focuses on the simple, everyday aspects of life, minimizing the author’s personal voice and literary ornaments to present a direct and realistic depiction of the world. Barthes’ analysis of naturalism is not merely a study of a literary style but also a reflection on broader cultural and ideological shifts in the 19th century, particularly in response to social changes and the rise of scientific thought. By striving for a “neutral” form of writing, naturalism embodies an attempt to capture the world as it is, devoid of subjective interpretation. Barthes uses naturalism as a key example to explore how writing seeks neutrality and how these efforts are shaped by historical and social contexts.

The Socotra Dragon Tree, in its natural, unembellished form, can be seen as a botanical counterpart to Barthes’ concept of zero-degree writing. Just as naturalistic writing seeks to strip away the author’s influence to reveal the world plainly, the Dragon Tree, with its unique and unaltered appearance, represents a natural state that stands apart from human intervention, embodying a form of neutrality in the natural world. Both the Dragon Tree and zero-degree writing share a commitment to a form of expression that resists ornamentation and highlights the essence of existence in its purest form. Perhaps the trees of the Socotra Archipelago in the western Indian Ocean can be introduced in nature through this writing style. “The Socotra Dragon Tree is a rare species with a thick, cylindrical trunk. At its base, it has a conical shape with leafless branches. The tree’s leaves are lanceolate and needle-like, concentrated at the ends of the branches, giving the tree’s crown a canopy-like appearance. The trunk’s bark is grayish-brown, and when injured, a red resin known as “dragon’s blood” is released.”

I ponder, do they not perceive the beauty in language, simple and unadorned? A chill grips my heart at the thought that poetry itself might be the curse that haunts my homeland.

- Dedicated to Inès D.

[1] – Bonsai is the traditional art of growing and meticulously shaping small trees in containers, designed to capture the essence of a full-sized tree in nature. This practice combines horticultural techniques with artistic vision, aiming to create a living miniature that reflects harmony, balance, and the passage of time.

[2] – Elliott Oring (1993). Victor Turner, Sigmund Freud, and the Return of the Repressed. Ethos, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 273-294 (22 pages). https://www.jstor.org/stable/640551

[3] – Heidegger, Martin (1996) Being and Time. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. State University of New York Press.

[4] – The Elephant Bush (Portulacaria afra) is an excellent choice for bonsai cultivation. This hardy shrub can reach heights of up to 5 meters in the dry, rocky terrains of South Africa, yet in its natural form, it looks quite different from the meticulously crafted bonsai trees.

[5] – McKenna, T. (2011). Hegelian Dialectics. Critique, 39(1), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03017605.2011.537458

[6] – Freud’s concept of “the Return of the Repressed” is based on the principle that repressed thoughts and desires, which have been kept away from conscious awareness, reappear in altered forms such as symptoms, dreams, or slips of the tongue.