From the Coffeehouse School to Wandering Through Cafés – An Examination of the Work of Rashin Ghorbi

- by Behnam Shah-Hosseini

- Guest Contributor

Offered my soul as a vessel for your lips, dreaming

That a drop of that pure essence might touch my own

Alas— ‘craft us no lures’, your tresses whispered

‘For many such prey is caught in our snare’(Hafez)

My father never cared much for social gatherings. He wasn’t one for friendly hangouts, not even the cafés and coffeehouses of 1960s Tehran. My grandfather, however, was different. He loved cinema, theater, and cafés. He would take us, his grandchildren, to the movies—mostly foreign films—once a week.

Beyond that entertainment routin, there were also wandering storytellers who recited the Shahnameh. Sometimes, I would hear the recitations in coffeehouses. Television channels aired naqqali[i] before children’s programs as well, but it never gave the same magic as the traveling storytellers. The audience for those public performances was always the local community.

The storyteller’s resonant voice still echoes in my ears, and the painted curtain stands vivid before my eyes—a living memory. The experience was astonishing, like a book come to life, clutching my imagination. The images depicted an entire world—strange, grand, distant, yet monumental. They wove mysteries in my mind. Ones I could never unravel. They were music, lingering with me long after.

What I witnessed, was the last generation of painted curtain storytellers. Five decades have passed, and my only remaining connection to those days is the paintings—silent now, without the storyteller’s voice.

Though nothing today is quite like the past, for me, the memories of childhood came alive again—through the story of new saints and villains in Rashin Ghorbi’s paintings[ii]. Her narratives, much like those of the naqqals, exist more in the realm of imagination than reality—a fantasy that can be seen and believed.

Imagination, a Path from Within to Collective Memory

Imagination finds its way through unconscious memory. The more you surrender to it, the farther it takes you. And yet, this journey is not bound by the concepts of the abstract—it will not necessarily be about peculiar or surreal beings and spaces. In truth, much of what we see every day exists within imagination and often merges with it.

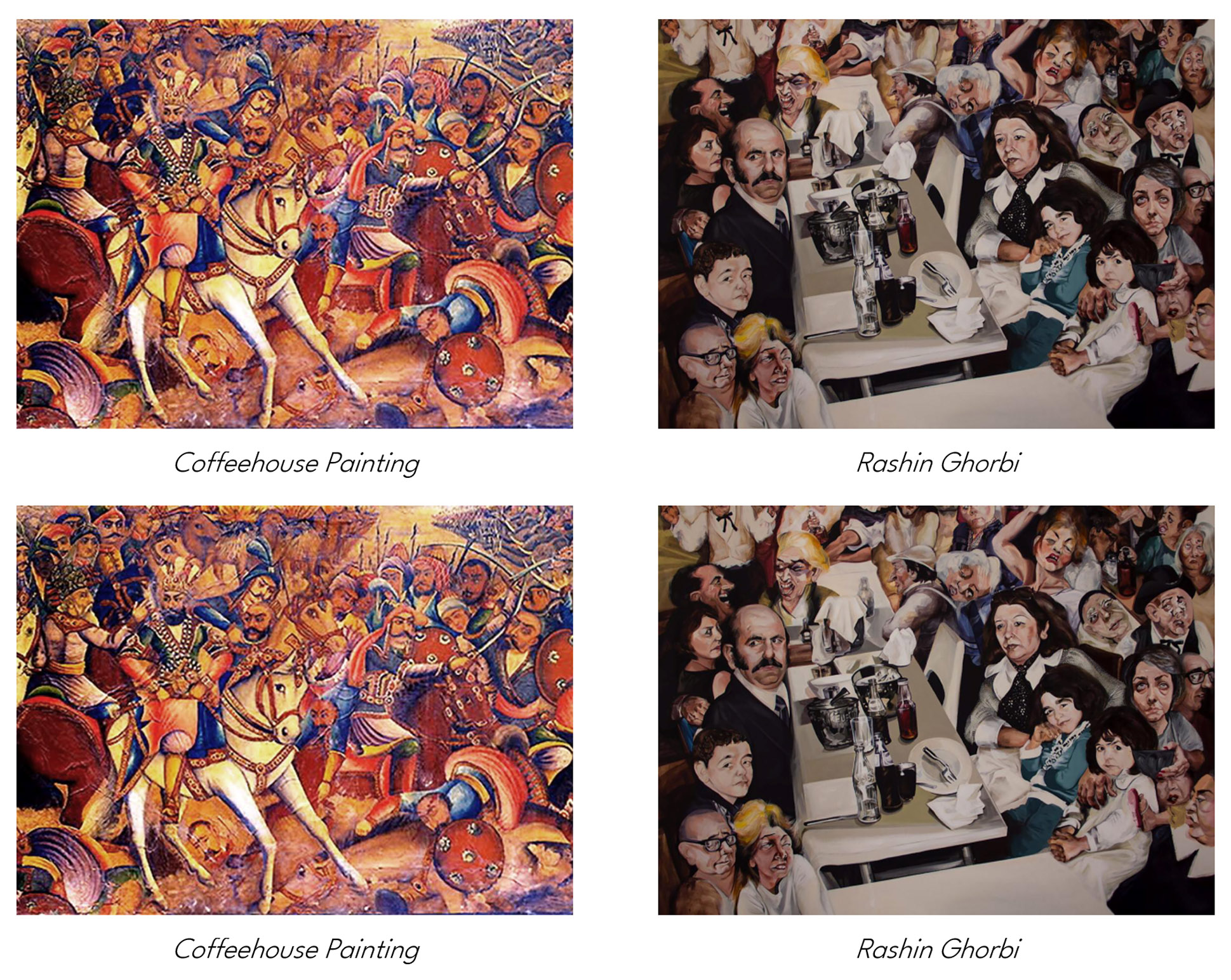

If this collective unconscious memory is given some freedom, it takes its own course.[iii] The structures that emerge from this collective unconscious share a certain harmony, yet the artist’s individuality remains fully visible within them. This is the essence of what can be grasped when comparing Ghorbi’s works to coffeehouse painting.[iv]

Imagination does not work conditionally. Categorization under various isms and market-driven approaches claim the artist’s soul. Isms serve history well, but not artists. When they take over, they become new ideologies, turning the artist into a captive. What should be the artist’s existence becomes servitude to nothingness. The excessive consumption of these trends and isms—along with the disregard for the artist’s individuality and their connection to their own assets (their personal and collective unconscious)—drags everything into the swamp of mediocrity.

Ghorbi’s work is not a coffeehouse curtain. No viewer perceives it that way, and that is precisely what makes it distinct and contemporary. This structure is embedded within her paintings—hidden, even from her own consciousness. Avoiding self-awareness is, in itself, unconscious. Her only true awareness lies in her mastery of painting and design, her attentiveness to her surroundings, and her disregard for isms and artistic trends.[v]

Sword-Wielding Figures of the Coffeehouse and the Unarmed, Restless Faces at the Café

Looking at Rashin Ghorbi’s works, I feel as though I am seeing coffeehouse painting in the present—though without the storyteller—where the figures themselves cry out. In traditional coffeehouse paintings, faces remain calm, even when adorned with weapons and armor, conveying their narratives through names and symbolic gestures. In contrast, the faces in Ghorbi’s works are expressive, loud, and full of character.

She does not imitate coffeehouse painting—neither in content nor in form—yet its structure and essence remains. Many artists who borrowed from Iran’s artistic past misstepped, reducing it to misleading caricatures through superficial stylistic choices. But perhaps Ghrobi, by not reconstructing the past, has succeeded where others failed.

Her works are not a continuation of coffeehouse painting, nor are they a modernized version of it. Instead, her paintings have unconsciously woven themselves into the lineage of Iranian art, carrying it forward.

There are several factors that have contributed to this achievement.

Judgment and Non-Judgment

One of the fundamental elements woven into the essence of Iranian painting—binding its works together like a strong thread—is non-judgment. Non-judgment is a form of knowledge that reveals its meaning in the future. Since we are unaware of what lies ahead, it is wiser to remain without judgment. When we become aware of an event, we fall into folly and judgment. Woe to the day when a world full of contradictions fails to reconcile.

All beings, in their existence, return to a universal essence. When viewed without judgment, faces appear similar—yet this does not negate individuality.

It is like the pottery Omar Khayyam speaks of: “… shaped and then shattered upon the earth.” It is the human condition—one whose differences remain unknown. But the closer we come to this existence, the closer we approach unity, and temporal differences diminish. It is as if all eras collapse upon one another, and the past is determined within the future.[vi]

For every painter, perception is shaped by their unique artistic model. In Ghorbi’s works, all figures converge into their turbulent essence within the “overlapping of time”, forming a collective presence.

Ghorbi exaggerates all characters to the point where they become alike—except in certain cases where she makes exceptions for specific individuals (the hero in the work). Either they are all shouting, or they are engaged in conversation. The result of all this intensity is, ultimately, silence. A storm that has settled, leaving destruction behind—one that must be rebuilt with patience and endurance.

She leaves her heroes alone within the artwork, facing this catastrophe. Like the painted curtains of coffeehouses, they are either victims and oppressed yet dignified, or conquerors—aloof and indifferent. Because here, everything neutralizes itself, and in the end, silence is all that remains. All of this is the effect of non-judgment, which stems from the nature of time.

One of the striking aspects of Ghorbi’s work—its non-imitative yet astonishing overlap with coffeehouse painting—lies in the compression of figures and faces.

Many artists have tried to avoid this overlapping composition, fearing the mark of imitation. Others have attempted to merge collages of the past with fragments of modern art, only to produce sterile results. Some have reshaped Middle Eastern artistic references into new forms, but their efforts often led to mere philosophical musings. Over time, the enthusiasts of these approaches grew disillusioned, and now, a silence has emerged—perhaps for the better.

It may be best, in this historical gap, to simply work and create. In doing so, something will emerge—something honest, something that embodies the spirit of our time, growing from the individuality of painters. Some have already done this, and others will follow.[vii]

The compactness of faces in Ghorbi’s work does not resemble a photographic composition. Instead, it arises from a visual arrangement of grouped figures—a collective whose shared essence brings them closer to a unified perspective. Even in pieces where some figures appear smaller and more distant, colors and forms reinforce their connection, strengthening their bond.

Her recent works seem to have matured over time. She has solidified her compositional structure, refined her spatial arrangements, and given her characters greater physical presence. Furthermore, in both Ghorbi’s paintings and coffeehouse art, figures and elements either orbit the central narrative or follow its lead. This approach not only enhances the grouping of characters but also reinforces the core theme—a technique deeply embedded in traditional coffeehouse painting.

The Significance of Theme and Structure

At its peak, Rashin Ghorbi’s pieces can be compared to the pinnacle of coffeehouse painting, and this comparison is precisely what is presented here as an example.

Analyzing the visual structure of her paintings alongside coffeehouse painting reveals how deeply connected the two traditions are—despite their distinct approaches. While her method of execution differs, it retains an essential kinship with coffeehouse painting, yet tells a different narrative—one shaped by time, no longer bound to the conventions of coffeehouse art.

The sacred essence of coffeehouse painting is inverted in Ghorbi’s works. Instead of descending from above, it now rises from below, reshaping figures with all their distortions and irregularities. Of course, this structural alignment is a unique case; not all compositions follow two conceptual foundations simultaneously. However, this structural resemblance is not the result of a stylistic choice—it is rooted in tradition, approached with creative innovation.[viii]

In terms of color tone, as observed in the third framework of analysis, a noticeable difference emerges. The colors in coffeehouse painting are generally warm or balanced between warm and cool tones, following a moderate color value. However, in Ghorbi’s works, the colors tend toward cooler shades, with greater contrast in values. This cooler palette can be attributed solely to the mood of this phase in her life.

Additionally, Ghorbi’s pieces are narrative-driven. The tradition of storytelling in Iranian painting and mural art is deliberately reflected in her work.[ix] She portrays café gatherings, night dwellers, and friendly circles, yet unlike the past (as seen in coffeehouse painting), these scenes do not pursue a specific goal—instead, they mirror the present moment.

The chaos in her paintings stems from the confusion of contemporary humanity—a turmoil in faces, a disruption of disproportionate limbs, intruding into spaces where they are least expected.

The main point of divergence between coffeehouse painting and Rashin Ghorbi’s creations lies in the use of hierarchical perspective, which is prevalent in traditional coffeehouse art.

Ghorbi employs a bold and risky technique, depicting her hero within a protective radius, visually separating them from others while rendering them with a distinct treatment. The risk lies in the fact that even the slightest miscalculation could split the composition, disrupting the coherence of character portrayal.

This also raises a conceptual question: Is Ghorbi positioning her hero within the realm of mythical figures from the past?

The last school of Iranian painting that remained interwoven with its past while embracing the innovations of its time was coffeehouse painting. At its core was non-judgment, just as had been the case in various artistic traditions before it. Additionally, the absence of an observing gaze played a significant role in shaping its essence.

However, in Ghorbi’s works, both the observer’s gaze and the figures within the painting are present—they look directly at us. They seem to say: We are incapable of unity on any subject, nor of judgment—are you?

When I look at her paintings, I do not dwell on the past. I know that the thread of history extends into the future—a future that arrives with every passing moment, breathing life into me. It is something akin to hope, the very essence of existence.

It is as if hope is a debt that Ghorbi borrows from the past, only to cast it forward into the unknown.

Endnotes

[i] Naqqāli, or Iranian storytelling, also known as Parde-khani, was the oldest form of recounting legends in ancient Iran, lasting until the late Qajar era. It played a significant role in preserving and passing down cultural heritage. The naqqāl would narrate epic tales—stories of Iran’s kings and warriors.

[ii] In Iranian Sufism, Awliya (saints) are revered as sacred figures, while Ashqiya (villains) stand in opposition to them. These two forces are locked in an eternal struggle, representing the ongoing battle between righteousness and wickedness.

[iii] With the presence of these energies, which arise from repressed desires, an escape route is found by directing human forces toward spiritual activities, such as artistic, scientific, technical, and literary pursuits. This state is known as “purification“ or the sublimation of human energy— (Page 15 from The Unconscious and Freud’s Psychoanalysis by Jean-Paul Charrier, translated by Dr. Seyed Ali Moḥadeth, published by Nokteh Press.)

[iv] From a psychological perspective, if a thought exists only in the mind of a single individual, its existence is purely subjective. However, to the extent that this thought is acknowledged and collectively agreed upon by a significant number of people, it also attains an external and objective existence.

(Page 4 from Psychology and Religion by Carl Gustav Jung, translated by Fouad Rouhani, published by Pocket Books and Amir Kabir.)

[v] … Neither a linguistic work, nor an aesthetic theory, nor an act or reality tied to taste can fully accomplish the task of art criticism. … Consider, for a moment, Baudelaire’s judgment of Delacroix: where the spiritual essence of art is at play, Delacroix’s taste is historically defined. His taste is not only distinguished from Neoclassicism due to its Romantic nature, but his fresh and innovative interpretation of Romanticism is also distinct within the movement itself. It is precisely here that the individuality and creative identity of the artist are recognized. (Page 30 from History of Art Criticism by Professor Lionello Venturi, translated by Dr. Amir Madani, published by the Scientific and Cultural Institute of Faza.)

[vi] Belated understanding: The delay in wisdom—the realization of an event only after it has occurred.

(Page 214 from Bundahishn Hindi, translated by Roghayeh Behzadi, published by the Institute for Cultural Studies and Research.)

[vii] Various authors have recently clarified the social origins of sacred temporal rhythms (e.g., Granet, Mauss). However, it cannot be denied that the weight and cadence of the cosmos have also played a dominant role in the discovery and organization of these systems.

(Page 366 from Treatise on the History of Religions by Mircea Eliade, translated by Jalal Sattari, published by Soroush.)

For further reading, see theories on time in quantum physics and Einstein’s general relativity in Parallel Worlds by Michio Kaku.

[viii] This is the same smoother and fresher source from which the Iranian soul is nourished, so that each time its historical thread is severed, it may rediscover its connections, identity, ancestral memories, and the treasures left as its heritage.

(Page 78 from Mental Idols and Eternal Memory by Dariush Shayegan, published by Amir Kabir.)

[ix] Alongside Symbolism and Portraiture